Robert Caro’s growing multivolume biography of Lyndon B. Johnson is a lesson in how to do biography as history, and one in how power works in the American political system.

Once what is likely to be the last volume of The Years of Lyndon Johnson, number five, is unpacked in bookstores and pushed out to Kindles and iPads everywhere, Robert Caro will have been at it for over four decades. When exactly that will be is still unclear, and I am not holding my breath. In 2012, Caro predicted it would take another two or three years. (“But why would you believe me,” he joked in a Guardian interview that year).1 It’s now 2016 and there hasn’t been an announcement. Caro’s ever-expanding research has turned what he once predicted to be three volumes into a now expected five, and made the third book, 1992’s Master of the Senate alone easily three books’ worth in size. Book reviews through the decades are thick with words like “magisterial,” “definitive,” “sweeping,” “masterful,” even “majestic” when they describe volumes of Caro’s Years. Less favorably, a Salon.com review of volume four called Caro’s biography “bloated.”2

If you’re only a little bit interested in power and the American political system, today and during the twentieth century, you should read the books. They are engrossing, and they are helpful reminders that deadlock in the US Congress and pandering political manipulation are nothing new. They are also, however, nothing eternal and unchanging. They are tied to historical contexts and historical actors. Institutions matter, but people matter as well. People who can shape, change, and dominate these institutions. Reading or re-reading Caro’s Johnson is an exercise in reminding oneself that history is never just about one thing. It’s not about academic arguments alone, or just about the political uses of the past. It’s messy, and fascinating, and alive.

The Books So Far

The series consists, in mostly chronological order as far as the “Years of” are concerned, and in order of publication, of The Path to Power (1982), The Means of Ascent (1990), Master of the Senate (2002), and The Passage of Power (2012). It’s worth listing them here. Despite Caro’s considerable craft with words, and a publisher who has preserved the integrity of the series throughout, the titles only really speak to the place of each book in the whole story after you’ve read them all.

The Path to Power is the origin story. Caro vividly depicts the hardscrabble life of generations of Buntons and Johnsons, the two families of LBJ’s forebears, in the Texas Hill Country. He describes the emergence of Johnson’s deepest fears and most destructive personality traits, the less than idyllic country boy life, and the barely adequate education Johnson received. The shame he felt when his family, driven by Johnson’s father Sam’s romantic imagination, lost everything and had to live on the charity of townspeople. The Johnsons of Johnson City had once been respected, but as Lyndon Johnson grew into a man, they no longer were. Caro stresses the contrast between young Lyndon and his father, an idealist who Lyndon had once sought to emulate. No more. This all adds up to the making of a maker. Of a liar and abuser, for sure, but an occasional and effective advocate for the downtrodden all the same. There’s ample foreshadowing here for Johnson’s eventual turn as the last great reform president of the twentieth century. Ample as well is the back story to the situation in the Hill Country, a “hard land” that broke dreams, a place which Lyndon Johnson’s brother Sam Houston Johnson describes as “lonely” and where entertainment of any sort was hard to come by. “On the rare occasions on which a movie was shown, there was as much suspense in the audience over whether the electricity would hold out to the end of the film as there was in the film itself,” Caro writes.

On the many changes that electrification and the building of better roads brought to rural America, the book presents little new information. Yet, Caro’s evocative prose detailing the drudgery of Hill Country housewives on wash day and, the worst day of them all, ironing day, may just amount to a reader finally, for the first time, actually empathizing with what the change meant for the people it affected. Emotions are Caro’s trade, and he spends long pages detailing the process of heating and re-heating the “sad irons” over a sooty fireplace, and the sweat and disappointment this work brought with it. Canning and the preservation of fruits and vegetables, practices tinged today with hippie-hipstery faux nostalgia for a pastoral never-neverland, are described painstakingly as the survival necessities they were. Path follows Johnson through his college years and his early career as a Congressional secretary, and ends with him ensconced safely but unhappily in the House of Representatives after losing out on his first bid for the Senate.

The Means of Ascent is the book about money, though the “means” here is clearly employed in both senses. It is the shortest book to date, at a “mere” 506 pages (first edition). It is here that Caro shows how Johnson, through smart and borderline – if not downright – illegal, maneuvering involving inside connections to the FCC, turned an also-ran radio station into a powerhouse. His media empire (on paper his wife’s) would eventually encompass a television station as well. Buying advertising time on a Johnson station was the surest way of making sure political favors would follow.

It’s a book about morality and about amorality, and it usually finds Johnson on the side of the latter. The main showdown is between Coke Stevenson, beloved Texas governor and shoe-in senatorial candidate, and Lyndon Johnson, unlikely challenger, three-term Congressman from an almost inconsequential district in the remote Hill Country. The story is how Johnson takes down Stevenson with all the dirtiest tricks, and then goes to Washington on only 87 very clearly faked votes. “Landslide Lyndon” prevails through the following legal tribulations with only the thinnest margin for error, but prevail he does.

Means is the volume in which Caro starts really putting “vignette biographies” – notably of “Pappy” O’Daniel and Coke Stevenson – to good use. These chapter-sized excurses could easily be taken out of the books whole and stand on their own, as likely the only thing you’ll ever need to read on the person concerned. (Later books contain such vignettes on Richard Brevard Russell, and both John F. and Robert Kennedy. Some reviewers have panned these as unnecessary and unoriginal, but Caro is a completist, and these tangents always branch back into the ongoing narrative, like tributaries to a river.)

Means of Ascent is the book in the series that has been most controversially reviewed. Caro pretty obviously sides with Coke Stevenson on the senatorial race and ensuing legal battle. Stevenson, we are made to believe, clearly had the law on his side. The wide angle isn’t quite so clear cut, however. Stevenson was also a rabid segregationist, and was not entirely above the wheeling-dealing of Texas politics himself. Caro restates again and again that, even following the loose standards of morality then prevalent in Texas politics, Johnson went too far. But when does a difference in degree become a difference in kind? And, this is a question which he treats only cursorily but which touches on the heart of Caro’s project, what of the greater good? Would America have been better off without Lyndon Johnson in the Senate? And, consequently, without Lyndon Johnson as president, shepherding the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act to eventual passage? Once again, it is a question of means and ends. Any answer can only be uncomfortable, but that is, precisely, the ground on which politics thrives.

Master of the Senate is the centerpiece, both of LBJ’s life and the series. Not for nothing for a man whose official presidential portrait shows him, all wistful cunning, backdropped by a luminant sky and the US Capitol, not the White House.

It is the book that, according to Caro, explains his interest in LBJ. Not his presidency, not a stolen election or other amoral dealings in politics and business, Johnson’s years in the Senate are what brought the author to his man. It is also the book with the clearest message and the most convincing array of arguments. Caro does not do this by throwing up mountains of evidence that point in one direction, but instead by, incident for incident, crawling through the corridors of power with Johnson. The thesis is clear: The Senate was dysfunctional, and only because Johnson grasped for every bit of power that he could, did it become a mover in American politics, and not remain an immovable object. LBJ – he himself wanted to be known by his initials, making clear a connection and a hoped for equality of stature with FDR – played his connections to Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn and to Old South racist and strategist for the Southern Democrats Richard Russell in order not only to gain to power, but also to get things done. Richard Brevard Russell (“of Georgia” one unwittingly adds in one’s head when hearing or seeing that name after reading Master of the Senate) also gets the Caro vignette biography treatment. Impressively racist for any age, Russell is the perfect foil for LBJ in this episode. After Johnson haltingly enters the big fight over the 1957 Civil Rights Act at the end of Master, Russell still holds the power to derail him. That he does not is due to a combination of Johnson’s knack for reading people, of tactics, and of his relationship with Russell. Russell, who likes Johnson, and still thinks of him as the Southern senator with the solid segregationist voting record who began his senate career with a fervently anti-civil rights “We of the South” speech. Johnson didn’t throw himself into that fight immediately, but when he did, he moved the levers that needed to be moved. Implausibly, he also got the first civil rights bill in three generations passed while still standing in relatively good stead with Southern Democrats, lead by Russell.

The Passage of Power is a bit of an odd duck in the lineup. Still, it’s the book you’re most likely to reach for if forced to pick only one: it contains the most important moments of LBJ’s journey to the presidency. It details the transition following Kennedy’s assassination (a part that was also spun off into a much slimmer book), when Johnson took power in a most decisive way. Before that moment, however, we are treated to Johnson’s indecisiveness about entering the 1960 presidential campaign. When he finally decided to jump in, it was much too late; all he could do was grab hold of the number two spot on the Kennedy ticket. Vice President Johnson appears to have been useful to Kennedy only for winning in the South. After that, “Rufus Cornpone,” as Kennedy staffers called Johnson, was put out to pasture, buried under the ceremonial blanket of representative duties at home and abroad. His attempts to hold on to power in the Senate having failed, and utterly despised by Robert Kennedy, Johnson in this part of the story is almost to be pitied. The transformation after Kennedy’s death, however, is complete. Johnson holds on to the reins of government, and, in passing civil rights legislation and the Great Society, accomplishes what he always wanted. “Power reveals” is the mantra. Johnson apparently always wanted to help out the little people. That’s a bit of an odd statement for Caro to make: Johnson as president finally can do and does what Johnson in no other role even attempted. In his telling, it’s as if the dam has finally broken. But, we are left to wonder, what if Johnson never had become president – a long shot goal for a rural Texas boy if ever there was one – but still tried desperately to gain power? Would he have gone on maneuvering in the background, helping himself to money and maybe, just maybe, some of the little people to a bit more dignity along the way? Would any of his maneuvering have mattered?

For Volume 5, as of yet no title is known. If we follow some tease-ahead remarks in The Passage of Power, however, it’s clear it will mostly deal with the rest of the Johnson administration. We should expect a detailed account of Johnson’s election, in his own right, to the presidency, and musings on his eventual downfall, the Vietnam War – also already foreshadowed in Caro’s description of Johnson’s war hawk stance on the Cuban Missile Crisis. (The telling of which Caro, as Fred Kaplan complains on Slate, gets woefully wrong.)3

This will likely be capped by a final chapter on Johnson’s retirement years on his Texas ranch, a period which always evokes a certain sadness: Johnson, with long hair that utterly reshapes his face, burying the once so dominant ears, as if burying his powerful persona as well, pottering about in the garden. A man who failed both at holding on to power, and at finishing the work he started in his Great Society program. Brought down, in both cases, by his need to appear strong, and his contention that America, too, needed to appear strong in Vietnam. What Caro will make of the end of the man he has followed for so long will certainly be worth reading.

It’s About Power

Power. The word comes up frequently throughout the series, so let’s talk about it. Power, for Caro is essential. In a 1990 Vanity Fair interview, he pointed out “History… isn’t history unless you show the effects of power.” Power is not, however, a top-down thing, not a club you wield, not a shower of influence you can just point and things will happen. His conception of power is almost Foucauldian, though there’s no reference to Foucault, and likely the French über-theorist had no influence on Caro. After all, Caro began his inquiry into how power actually works in a democracy, as opposed to the school chalkboard fairytale that it all ends with you, the voter and citizen as sovereign, when he began researching his first Pulitzer prize win, The Power Broker, in the 1960s. That book dissected the influence of Robert Moses on city planning in New York.

Karl Wolff, in a 2012 review of The Passage of Power calls Caro “a kind of Pop Foucault.”4 This would be essentially correct if Foucault himself wasn’t already the Pop Foucault (a Google search for each has Foucault’s name beat out Caro’s by a factor of more than 30), and if their conceptions of power matched more closely. Although their ideas are often parallel, the differences are important. Caro’s concept sees power as something a person can get and use, can amass and then apply and direct. It is what you eventually have when you, like Robert Moses or Lyndon Johnson, have a knack for finding it in hidden knowledge, in an innate understanding of specific people or general human nature, or tucked away in arcane rules. For Foucault, in the oft-repeated phrase “power is everywhere: not that it engulfs everything, but that it comes from everywhere.”5 That’s not to say there are not similarities. For Caro, as well as for Foucault, power does not originate as a top-down force, but instead is dispersed. In Caro, single actors come about and find such dispersed power, then they orchestrate and use it. In Foucault, power is constantly in a process of being negotiated, through pulls and pushes and parries and patinandos. Despite the differences, from a Foucauldian point of view, you could do a lot worse than read Robert Caro’s books: his understanding of power may not be the same as Foucault’s, but they are, up to a point, compatible.

And Language

No description of Caro’s Johnson would be complete without reference to the language in which the author puts his books. Caro cites Francis Parkman, the popular nineteenth century historian, bestselling author of The Oregon Trail, when he talks about how he needed to establish a “sense of place” for his book. In a larger sense, though, Caro’s whole oeuvre is a project to Parkmanize political biography.6 Like Parkman, Caro has lived in places he writes about, including the Hill Country. Even more so than Parkman’s, Caro’s cadences are musical. The sentences might often be run-on, but they want to be read. Need to be read. If you’re from the “only simple sentences are good” school, Caro may well make you re-think that assessment. His constructions are masterful, and you soon forget that the page you’ve finished has been scarcely more than one sentence. Caro strings together words in garlands, decorates them, repeats them, dotes on them, and finally lets them conclude at the point where they have been headed all along. Repetition is his favorite tool, and for the most part, he wields it well. So well, in fact, that soon you become engrossed in the story – in the detailed, meticulously researched accounts and psychologizing speculations – and would miss the saccadic rhythm that is its constant soundtrack if it wasn’t there.

The image of the conductor that Caro uses several times in reference to Johnson in the Senate is apt, too, to the author arranging his materials. The Senate, to Johnson was “the right size” as he is quoted in a memorable scene, taking in the view of the Senate floor for the first time. At 96 members at the moment of the future president’s 1956 accession to it (thanks to that famously stolen election), the Senate, Caro contends, offered a limited number of “texts” for Johnson, the “reader of men” to study. This Johnson did, and emerged during his first term as the single most able operator of that body for a century, and quite likely ever since.

Reviews of single volumes have remarked on either how negatively or positively Johnson is portrayed in one book or another. In The Path to Power he is a sniveling, repulsive powerseeker, a compulsive liar and a ruthless political manipulator, always intent on improving his position and berating his inferiors. “Almost without exception his [Caro’s] judgments on Johnson are not merely negative but hostile,” writes David Herbert Donald in his 1982 review for the New York Times.7 In The Means of Ascent once again all the worst of Johnson’s qualities, and seemingly only these, are on display. Master of the Senate is more even-handed. If “power is where power goes,” as Johnson himself was fond of saying, then it surely went to the Senate with Johnson.

In The Passage of Power the bad parts of Johnson’s personality are subdued, though not entirely excised from the narrative. The LBJ of the post-Kennedy transition is a careful, helpful man. A “hagiography of sorts” reviewer Karl Wolff calls Passage. But when you read the books in quick succession, the similarities in tone and judgment are much more striking than the differences. This similarity of treatment is, however, also both the strong suit and the greatest failure of all volumes of the series. In all books, Johnson is a veritable Jekyll and Hyde, and then some. But he isn’t his worst self and his best self and any gradation in between at the same time. Narratively, these Johnsons inhabit different worlds inside the books.

The Man and the Age

Caro sees Johnson as both a fascinating figure in his own right, but even more as a cipher for America in the twentieth century. LBJ is the face of “modern” politics – campaigning in Texas with a helicopter, making sure he gets the best Hollywood headshot photographer to take his portrait – and the “watershed” president, according to Caro, the presidency when the liberal belief that government had a role to play in bettering American and people’s lives, in a hop, skip and jump over the credibility gap found itself demonized, first by Nixon, and then for good by Reagan and by his epigones.

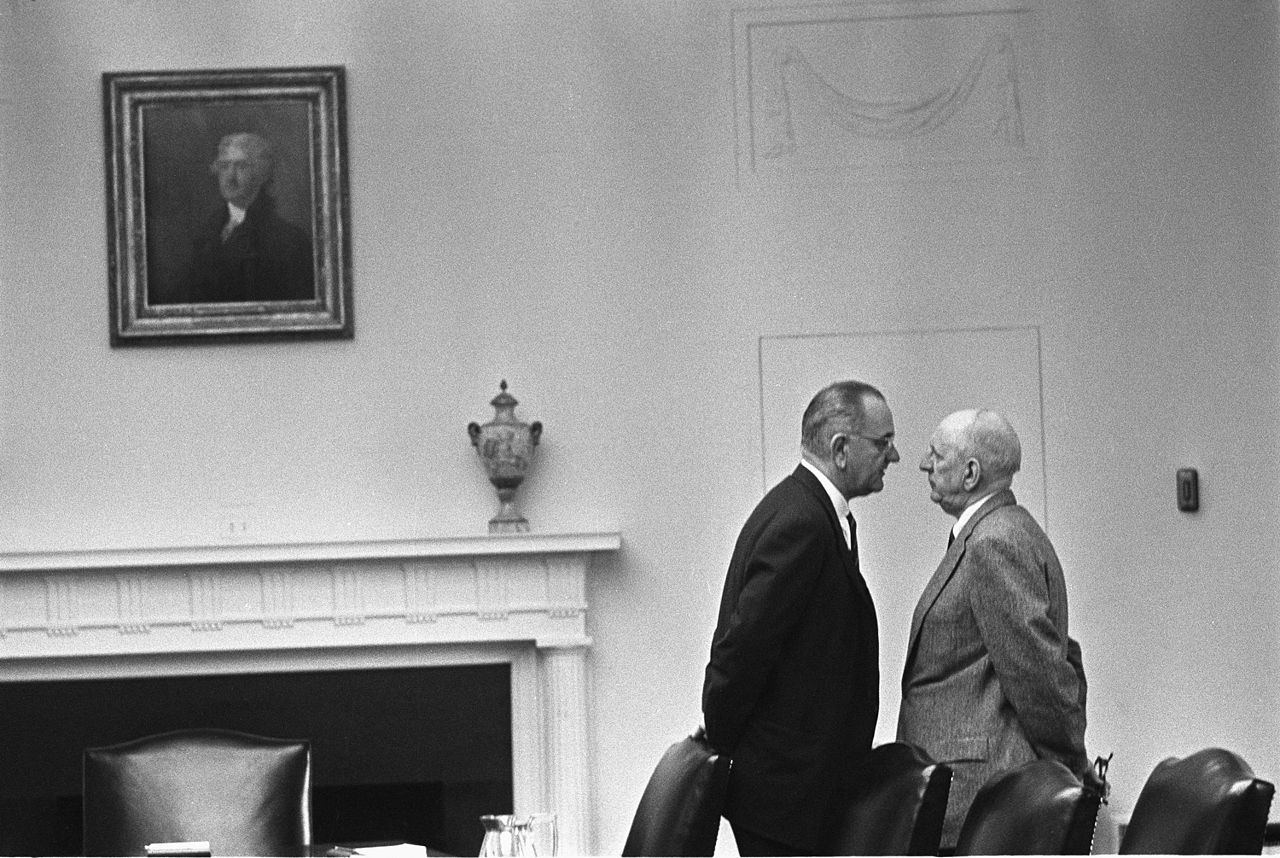

What makes Caro’s LBJ so compelling is his dumbfounding complexity. Caro, this too is reiterated in interview after interview, doesn’t particularly like his subject. But that does not mean he is not fascinated by Johnson. (Although he protests being “obsessed” by him.) As much as The Years of Lyndon Johnson is about the years, the period in which the man grew up and in which he exercised power, it is, of course also about the man. A towering figure, this Lyndon Johnson is. That he stood 6 foot 4 is repeated at strategic moments throughout the series. Johnson had, Caro tells us “the Bunton eye” or “the Bunton strain,” physical characteristics of the Bunton family from which he came, known across the Texas Hill Country towns of LBJ’s youth. Johnson was a person who used his size to intimidate and cajole, his overwhelming personality to charm and abuse.

The other man in the book is, of course, its author. Caro is interested in a very specific interpretation of power, and he enters into the record every last morsel that can help this end. His presence in the books is felt throughout. Reflective of changing academic style, the vague “a researcher” and the somewhat clearer “this researcher” or “this author” of the earlier volumes only give way to a tentative “I” in The Passage of Power, four books and more than thirty years into the project. The fact that this changes is interesting, but perhaps even more fascinating is that so little else does. Yet, the things that make Caro’s work over the decades consistent also make it less than inventive when it comes to any analytical category other than “power.” Despite LBJ’s major role in civil rights, Caro’s description of Johnson’s early years in the National Youth Administration during the New Deal, for example, is treated without any reference to race – though this is somewhat rectified in Master of the Senate, which also contains a stomach-turningly direct and effective description of the Emmett Till murder.

LBJ’s knack for pushing and prodding politicians to move, if just millimeters, their beliefs or their votes, at least, Caro holds as absolutely essential to the success of 1960s civil rights legislation, and to the Great Society program. These domestic successes changed the United States for the better, and Johnson deserves credit. But he also deserves blame for miring the US ever deeper in Vietnam. It is hard to imagine the United States in the late twentieth century, and even today, without either part of Johnson’s legacy. Civil rights on the one hand, the scars of disillusion that the Vietnam War left, on the other. It is impossible to imagine America as it is without acknowledging Lyndon Johnson’s impact. Even if Caro had done nothing more than point this out, it might be enough to justify spending over half a life and almost all of a career researching and writing about Lyndon Baines Johnson. The 36th president has been Caro’s conduit to show us the workings of American politics during an era when these workings mattered immensely. More power to Robert Caro.

- Chris McGreal, “Robert Caro: A Life With LBJ and the Pursuit of Power” in: The Guardian, June 10, 2012. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jun/10/lyndon-b-johnson-robert-caro-biography> ↩

- Erik Nelson, “Robert Caro’s Bloated LBJ Biography” in: Salon.com, May 7, 2012. <http://www.salon.com/2012/05/07/robert_caros_bloated_lbj_biography> ↩

- Fred Kaplan, “What Robert Caro Got Wrong” in: Slate, May 31, 2012. <http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/war_stories/2012/05/robert_caro_s_new_history_of_lbj_offers_a_mistaken_account_of_the_cuban_missile_crisis.html> ↩

- Karl Wolff, “Book Review: ‘Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power,’ by Robert Caro,” CCLaP, Chicago Center for Literature and Photography website, October 5, 2012. <http://www.cclapcenter.com/2012/10/book_review_the_passage_of_pow.html> ↩

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality. Volume 1: An Introduction. New York: Pantheon, 1978. 93. ↩

- To use Albert Hurtado’s fitting term. Albert L. Hurtado, “Parkmanizing the Spanish Borderlands: Bolton, Turner, and the Historians’ World” in: Western Historical Quarterly 26:2 (Summer 1995), 149-167. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/970186> ↩

- David Herbert Donald, “Up from Texas” in: New York Times, November 21, 1982. <http://www.nytimes.com/1982/11/21/books/up-from-texas.html?pagewanted=all> ↩

3 Comments